colour theory

georges seurat, d-day, and geologic time

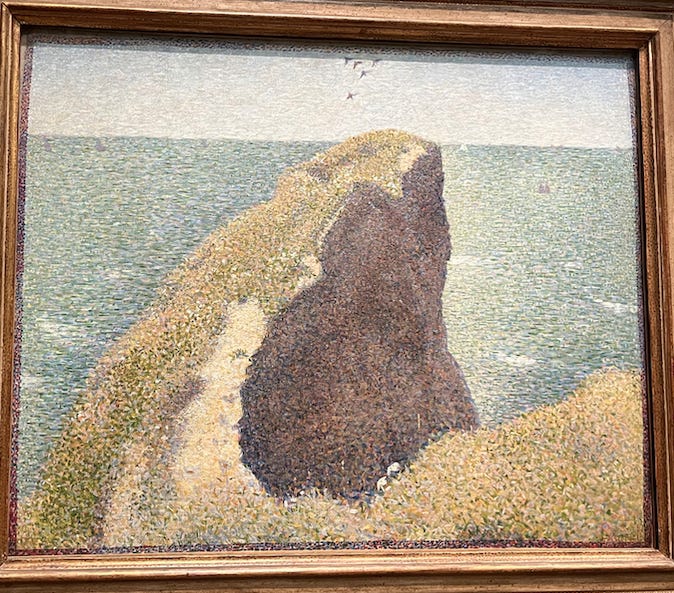

In the summer of 1885, when he was 25 years old, Georges Seurat painted Le Bec du Hoc, a dramatic rock formation on the coast of Normandy.

The year before, he had completed his first large painting, Bathers at Asnières, but it was rejected by the jury of the Paris Salon. Seurat responded by founding an independent salon with some other artists that would have no jury and no selection criteria, a place that welcomed and encouraged experimental art. Both Bathers and in Le Bec du Hoc are in the pointillist style, the technique with which Seurat is now principally associated and which, then, he had only just developed.

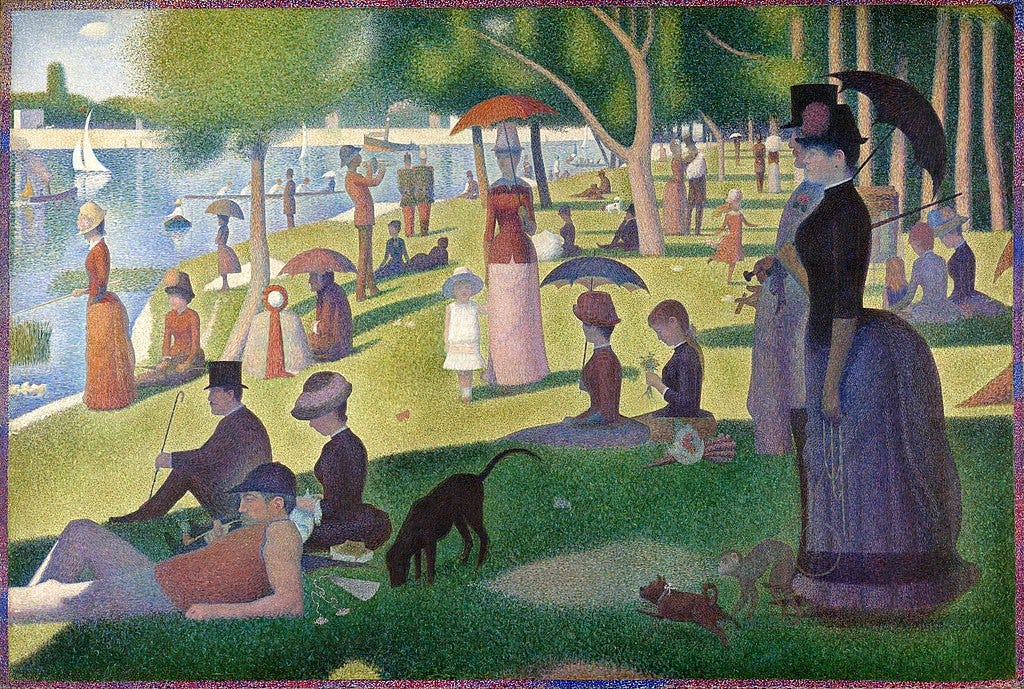

Perhaps the most famous example of pointillism is Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, which he completed in 1886, and which appears in that great American movie, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. In the film, the camera cuts between the painting and a dumbstruck Cameron, and every time it returns to the painting it moves closer and closer in on one little girl until her face becomes a collection of multicoloured dots from which it is impossible to discern even the shape of an eye or the line of a nose.1

A Sunday Afternoon is in Chicago but Bathers and Le Bec du Hoc are side by side in the National Gallery in London. If you look closely at the latter, you can see a border of dots, which Seurat added in 1888, three years after completing the painting, during which time he had studied deeply the work of men such as the physicist Ogden Rood, a pioneer of colour theory, the chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who researched textile dyes, and the mathematician Charles Henry, who became his friend. All of them influenced Seurat’s understanding and use of colour.

The dots he added to Le Bec du Hoc in 1888 are dark red and dark blue, colours that don’t appear at all in the pale summery landscape that the painting depicts — but the result is one of harmony. The same shades and a similar border reappear in A Sunday Afternoon — also added years after the painting was completed, in 1888 or 1889 — though here they are bolder and more assured, more striking. The border is startling in its modernity. There is a pleasing shock of colour contrast, and the effect of the “frame” and of those unnatural staticky shades running alongside the greens of the park and the blues of the lake anachronises the painting in some way — as if the dotted border, so reminiscent of pixelated television noise, thrusts the subjects of the painting into the conscious view of the future, from which vantage point we have, until we notice this strange and compelling perimeter which seems to be addressing us in our own familiar techno-visual language, been looking with cool historical detachment at the top hats, the parasols, the centaurian bustles and the monkey on a lady’s leash.

The cliff in this painting no longer exists. During the Second World War, the Germans built bunkers and machine gun emplacements on the promontory, which overlooks the English Channel. The allies bombed it in the lead-up to D-Day and the particular protrusion of rock that Seurat painted was destroyed. On D-Day itself, June 6, 1944, American soldiers made chaotic landings at the beaches below and then scaled the cliffs with rope ladders and grappling hooks while being fired upon by the Germans. Somehow most of them reached the top. Then the fighting began: two full days of it, at the end of which 90 of the 225 rangers who had set off from England were still alive.2

Like their cousins in Dover, the cliffs of Normandy are chalk, and in the geologic timescale date to the Bathonian age, during the Middle Jurassic period, when the land of the world was in the shape of the letter C: Pangaea had recently separated but the Americas, Africa, India, Australia and Antarctica were still one conjoined mass, thinly bridged by little Europe to the similarly entwined hulk of Siberia and China and Southeast Asia, and Tibet was an island alone in the middle of an ocean that no longer exists, a body of water called the Tethys Sea. All of this to say that the beak of cliff enshrined in Seurat’s painting had been around, perhaps underwater, not yet in its beakish form, but around nonetheless, for about 165 million years when it was bombed into dust during the Second World War; luckily for us, Seurat preserved it in paints.

Fifty-nine years before D-Day, the promontory was peaceful, not a pillbox in sight; Seurat lounged on the grassy bluffs and made quick studies that he would later use to paint Le Bec du Hoc. About 50 miles down the coast, Parisians strolled the promenade and crowded the seaside hotels of the resort town of Cabourg, which would later be immortalised as the fictional town of Balbec in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. In 1885 Marcel Proust was 14 years old, and hadn’t yet visited Cabourg; he went for the first time in 1907, hoping his poor health would improve by the sea, by which time Seurat, whom Proust, as far as I know, never mentioned in his various writings on art (Proust loved Impressionists like Renoir and Monet, who refused to show their work in the same exhibition as Post-Impressionist Seurat), had died, sixteen years earlier, of illness, at the painfully young age of 31.

The Battle of Pointe du Hoc, if you are interested in reading more.

"centaurian bustle"! unforgettable image. you write so well, have Ginko Season on preorder

I didn't know that about Tibet!