In The Fugitive, volume six of In Search of Lost Time, Proust writes that “grief is as powerful a modifier of reality as intoxication.” Grief changes our experience of the world; immersed in it, fantastical ideas can take on a semblance of the real. Sometimes we lose someone who is so close to us, or who was so “full of life”, to use the ever-apt cliché, that it’s hard to even understand that they’re dead. To put it another way:

You're alive, you're alive in my head

And if I didn't know better

I'd think you were singing to me now

If I didn't know better

I'd think you were still around

I know better

But I still feel you all around

I know better

But you're still around

This is Taylor Swift’s Marjorie, a song about her late grandmother. Like Taylor, the narrator of In Search of Lost Time also loses his beloved grandmother. When she first dies, though, he seems to have no reaction. It’s only long after, in a hotel they visited together, that the familiar surroundings trigger one of his many “involuntary recollections” and, more viscerally, the sense that she is in the room with him. He can feel her presence; he bursts into tears.

We store grief/love—when someone we love has died, the distinction becomes clouded—externally as well as internally, in specific types of weather, in smells and songs and objects, and oftentimes we don’t realise we’ve done so until we come across these talismans and they unspool our memories of the person we’ve lost. As Proust writes, in The Fugitive, of another loss:

it was my memory, made clearer by some intellectual excitement—such as reading a book—which revived my grief; at other times it was my grief—when it was aroused, for instance, by the anguish of a spell of stormy weather—which brought nearer to the light some memory of our love.

And in a very Proustian turn in Marjorie, a specific temperature felt one morning (in the present tense) sparks the recollection of long-ago events (and a switch to the past tense), a cause-and-effect process that happens over and over again in Proust, whose narrator is constantly thrown back into the past by a gust of wind or the light at a certain time of day.

The autumn chill that wakes me up

You loved the amber skies so much

Long limbs and frozen swims

You'd always go past where our feet could touch

And I complained the whole way there

The car ride back and up the stairs

A simple “autumn chill” is enough to unleash a whole sequence of memories of the loved one, and of an earlier time in the narrator’s life. Then we return to the present, but not to the present tense—instead, T.S. mires herself in the tense constructions which in English language lessons are referred to as the “modals of lost opportunity”—would’ve, could’ve, should’ve (incidentally, the title of another amazing Taylor Swift song). As their name suggests, these modals are custom-built for retrospective rumination:

I should've asked you questions

I should've asked you how to be

Asked you to write it down for me

Should've kept every grocery store receipt

'Cause every scrap of you would be taken from me

In “every grocery store receipt”, and, after that, in the memory or wish—it’s sort of ambiguous which it is—of having “watched as you signed your name, Marjorie”, there is a similar, though not identical, impossible longing to that which Proust’s narrator expresses in The Fugitive when he says, “I was driven to seek for myself occasions for grief […] in an attempt to re-establish contact with the past, to remember her better.” The words of both T.S. and M.P. palpitate with the anxiety of forgetting and the desire to preserve one’s memories of the lost loved one—remembrance as resurrection.

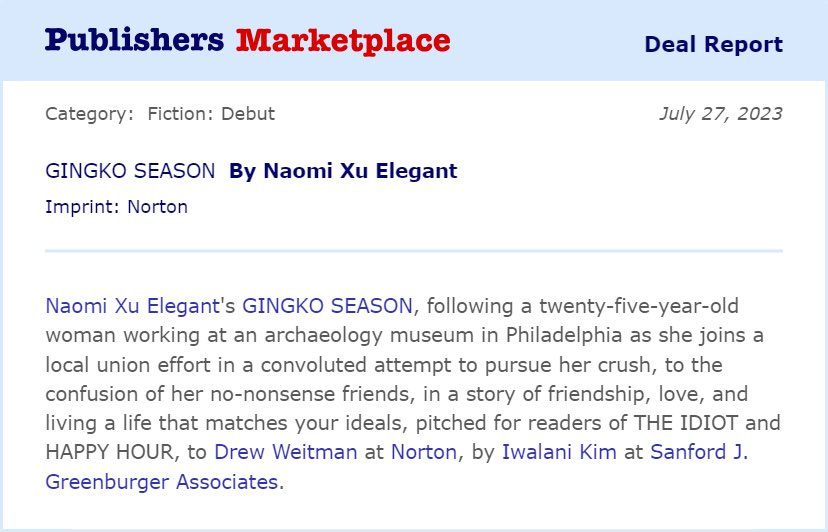

My book!

I wrote a novel; it’s going to be published by WW Norton in spring 2025. Norton is an employee-owned, independent publisher, and recently celebrated its 100th anniversary, which you can read about here. I’ll probably share more about the book starting next year, but here is the official announcement. In the meantime, follow @gingkoseason on Instagram!

Recent reading

The Moon and Sixpence by Somerset Maugham (portrait of a sociopathic genius artist, partly inspired by Gauguin), The Group by Mary McCarthy (love her…read this if you liked The Golden Notebook) and Main Street by Sinclair Lewis. Main Street was supposed to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1921, but the jury was overruled by the board because Main Street wasn’t “wholesome” enough (it makes snarky fun of ~American values~). Instead, they gave it to The Age of Innocence (another book I love, and the film adaptation by Scorsese is beautiful). Lewis was so mad that when he won the Pulitzer a few years later for a different novel, he declined it. He later became the first American to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, so it all worked out in the end. His Nobel speech is really good, and includes this great bit about the crazy changing world of 1930:

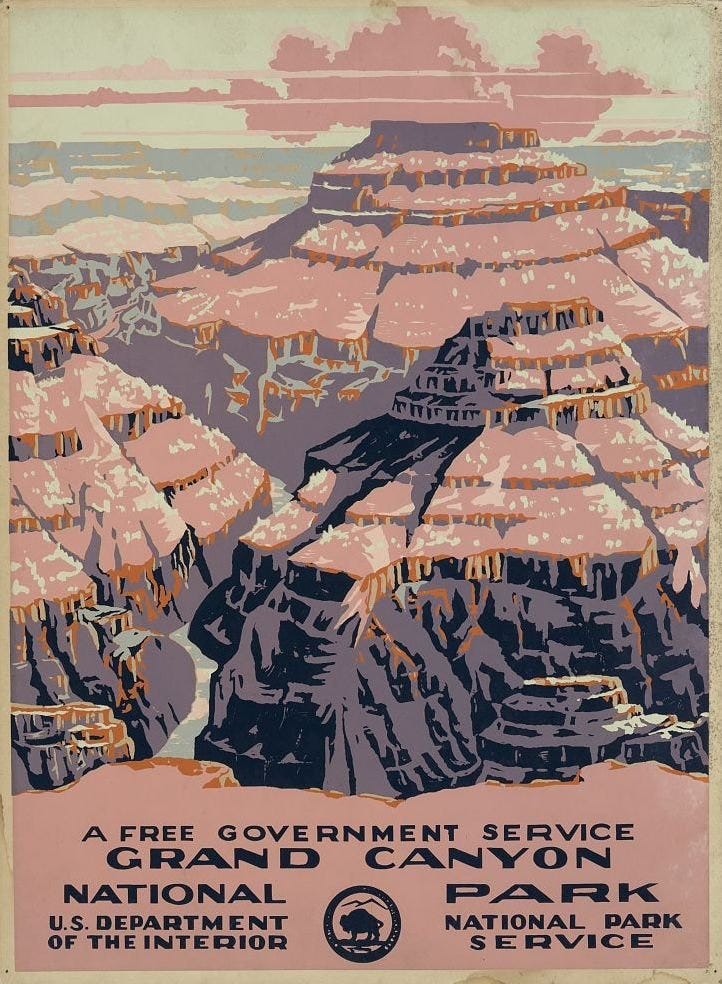

[…] for naturally in a world so exciting and promising as this today, a life brilliant with Zeppelins and Chinese revolutions and the Bolshevik industrialization of farming and ships and the Grand Canyon and young children and terrifying hunger and the lonely quest of scientists after God,

The reference to the Grand Canyon seems odd, because it’s millions of years old, but I think he must be referring to its establishment as a National Park in 1919, which led to an increase in visitors and probably a more prominent place in the American psyche. In 1919, 44,173 people visited the Grand Canyon; in 1930, when Lewis made his Nobel speech, 166,711 people visited; last year it was 4.7 million.

Finally, the best part of The Economist are the obituaries. They aren’t written in the publication’s usual tone (brisk, authoritative, snotty, depending on your outlook) but are full of literary flourish and emotional sensitivity. They stray into the philosophical but never the sentimental; they are a master class in the indirect lede and the punch-packing final line. Recently there have been some heartbreaking portraits of Ukrainians who’ve died in the war; more recently, I appreciated the obituary for Milan Kundera, whose work I really love. It ends with a beautiful image of him as a child, playing the piano. Anyway, here is a short and lovely profile of the woman who writes them all.

Thanks for reading!

Brilliant! I always found the scene where the Narrator recalls his grandmother perhaps the most moving in the whole book. The dead live on in the living. And I love the link to Swift btw.

Beautiful read as usual!