Welcome to luanqibazao, a monthly newsletter about literature, art, places, people, and cultural miscellany.

I recently acquired a book about the Singaporean Chinese painter Georgette Chen (1906-1993) whose mid-autumn still life appeared in my last post. It’s one of those big coffee table artist biographies, released as an accompaniment to a survey exhibition of her work at the National Gallery of Singapore that took place a few years ago. The book shares the title of the exhibit: At Home in the World.

Georgette was born in Zhejiang but moved to Paris with her family in 1914, when she was eight, and attended the Lycée Jules Ferry. In 1919 she transferred to Horace Mann in New York, and then to Shanghai to the McTyeire School, a private girls’ school run by American Methodists (its alumnae include the Soong sisters). After that, she moved around and between Paris, New York, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Penang, before settling in Singapore.

I’m fascinated by this generation of diasporic Chinese – the post-Qing, pre-civil war, pre-Japanese invasion, polyglot intellectuals for whom China was an ideal as much as an actual place they often returned to live and visit (the movement of the elite diaspora being by no means one-directional, and pre-1949 borders being much more porous) and who were comfortable flitting between languages, cultures and continents. Georgette is one example; another is her first husband, Eugene Chen, a prominent diplomat in 1920s Republican China. Eugene was born in the British Caribbean colony of Trinidad and grew up speaking English at home. He studied law and then worked in London, where he met Sun Yat-sen. Sun convinced him to come to China to help build the new government, and Eugene hopped on the Trans-Siberian railway to Beijing. On the train (or perhaps back in London, sources differ) he met a Malayan Chinese doctor who helped him choose a Chinese name, Youren, since he still didn’t have one. Amazingly, the doctor was Wu Lien-teh, who you may have read about in 2020-21 – he’s the guy who basically invented face masks after figuring out they prevented the transmission of respiratory illnesses, cough cough.

Wu Lien-teh and Eugene Chen led their lives within that exhilarating and sadly short-lived historical moment, and I encourage you to read more about their accomplishments and struggles. Eugene appears as a background character in Tim Harper’s excellent book Underground Asia, and there is a lot of good writing online about Wu, especially after the pandemic sparked new interest in his achievements.

Georgette and Eugene wed in Paris in 1930 (Soong Ching-ling introduced them!) and she painted many portraits of him. He was enthusiastically supportive of her career and art and they were happily married until his death from tuberculosis in 1944, while the couple was under surveillance by the Japanese in occupied Shanghai. In her paintings of him, he’s often holding a book, or maybe his glasses, with a hand against his forehead or chin, bearing a thoughtful frown.

Georgette’s father Zhang Renjie, a prosperous businessman, early anarchist, KMT supporter, and talented calligrapher and ink painter (a typical ‘dudes rock’ combo of the era), wanted her to study Chinese ink painting, but Georgette wanted to train in Western-style oil painting. She returned to Paris in 1927 to study art at the Académie Colarossi, sketching nude models and exhibiting her work in the annual salons. Many other Chinese artists were in Paris at the same time, including Liu Kang (1911-2004), who like Georgette was born in China and lived in Paris and Shanghai before settling in Singapore. Georgette Chen and Liu Kang are now regarded as two of the most well-known representatives of the Nanyang school, the Western- and Chinese-inflected style of art that flourished in Singapore and had Southeast Asian people and scenes as its primary subject (nanyang 南洋 means ‘southern seas’, and it came to signify Southeast Asia during the period of mass Chinese migration to the region).

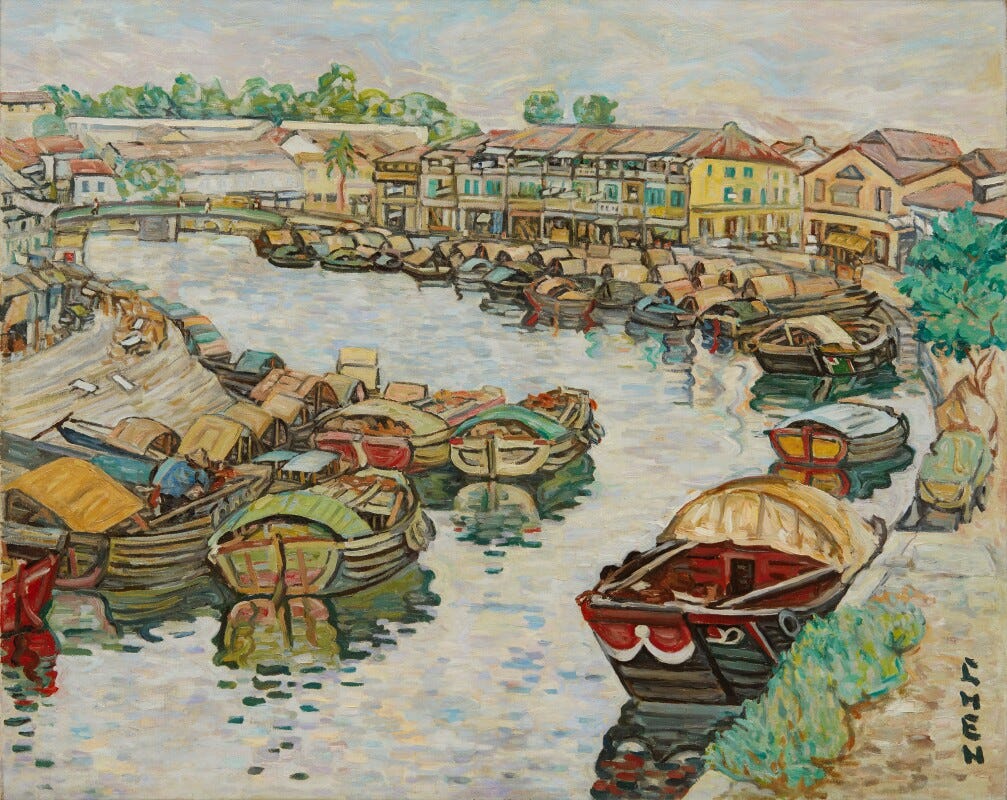

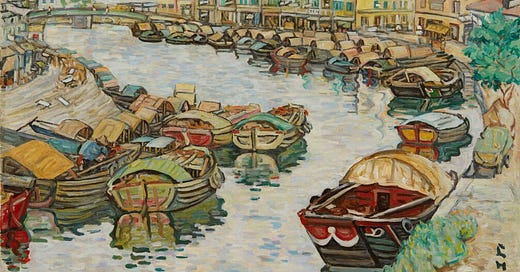

Here is one of Liu Kang’s paintings of Malaya. Matisse and Gauguin were big influences of his, which I think comes across:

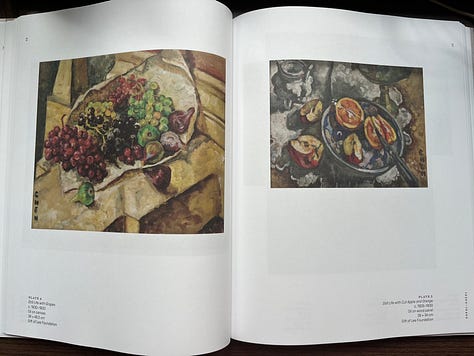

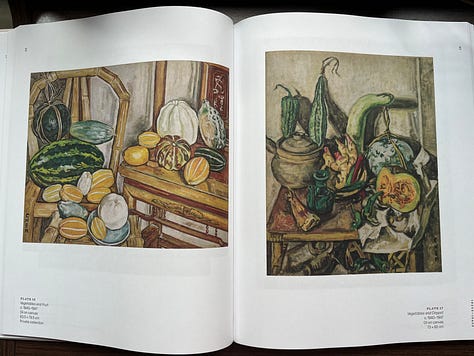

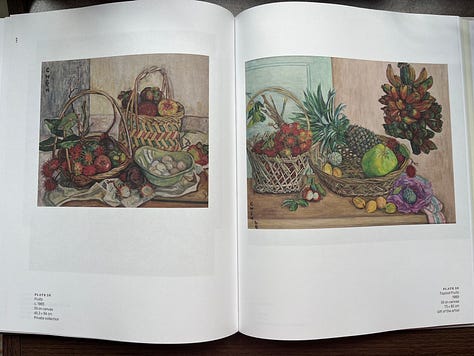

In France, Georgette painted the landscapes around her – Normandy, Brittany, Provence – and was influenced by post-Impressionists like Cézanne. Her paintings from the 1920s and early 1930s are skilfully done, but they are (imo) a little boring – competent pastiche, with none of the vibrancy and bold brushwork of her paintings of China and Malaya from the late 1930s onwards. A still life of grapes and figs, from 1930-33, is fine; another still life of various melons and gourds perched on Chinese chairs, from the 1940s, already feels so much more alive. By the 1960s, she is in Singapore, doing her famous paintings of rambutans, mangosteens, and all sorts of tropical fruits. She is so obviously so much more captivated by the tropical than the temperate, and it comes through on the canvas. The colors are bright and beautiful, and for me it’s a pleasure to look at also because when else have I ever seen a rambutan so lovingly rendered in oil paints?

Georgette Chen’s subjects included rice paddies in the New Territories, tin mines in Ipoh, canals in Suzhou, temples in Beijing, palm trees in Penang, Hakka families, Malay families, Indian families, Buddhist monks, Sikh guards, satay vendors, mosques, mooncakes, durians, bananas, Eugene Chen, Tunku Abdul Rahman, Wu Lien-teh (with a microscope, test tubes and a book labeled PLAGUE), and herself. This is a non-exhaustive list.

From the book: “[Chen explained] that her artistic trajectory involved a commitment to modern expression that conveyed contemporaneous scenes of life in China, something that she felt had never been adequately accomplished.” This expanded to the Nanyang region when she moved to Malaya – first Penang, and then, finally, after a short-lived second marriage, Singapore in 1953.

Georgette arrived in Singapore alone, a “displaced person … in search of a quiet place somewhere in Asia in which to rehabilitate and continue to paint”, as she put it. She called herself “the product of four historical events—all wars—two World Wars and two Chinese Revolutions, in all of which, somehow, I was inextricably and inexorably involved.” After a tumultuous, world-historical few decades, there was peace in Nanyang, and Georgette Chen stopped moving house.

She fell in love with Singapore, calling “my Tahiti”, a nod to Gauguin. She studied Malay and passed the government language exams, and even adopted a Malay nickname, Chendana, a playful combination of her surname and cendana, which means sandalwood. She taught painting at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. Georgette became a Singaporean citizen in 1966, just after Singapore became an independent country. She was 60 years old, and in the midst of the period in which she painted her most iconic works.

An early section of At Home in the World describes a group of Chinese artists, contemporaries of Georgette, who “rediscovered” China in the 1920s and 1930s through collections of Chinese ceramics and paintings in French museums. “Yet this did not lead to a return to a cultural nationalist position; rather these transnational artists selected and mediated elements from both cultures—Chinese and Western—to gain a fresh perspective on Chinese art and shape their own individual creative voices.”

Georgette existed somewhat apart from these artists (Lin Fengmian, Pang Xunqin and others), both socially and artistically, but she is certainly a transnational artist too. I’m inspired by her absorption of such a wide range of influences and the open-mindedness that she and others of her milieu – artists, but also political figures like Eugene Chen and Sun Yat-sen and medical pioneers like Wu Lien-teh – maintained towards Chinese and non-Chinese sources of learning, which they synthesised into new and flexible notions of Chineseness and art and governance and being (at home in the world). It was such a different time. Passports didn’t even exist until 1920! A Trinidadian with an English accent could become foreign minister of China, and to be a ‘Chinese nationalist’ meant that you were someone committed to progress, internationalism, humanism, openness and change – values, rather than a specific party, or language, or territorial claim. IDK JUST SOMETHING TO THINK ABOUT.

“…for these artists equipped with rich cross-cultural experiences and international visions, Chinese and Western art did not function in binary mode … both (as well as other art discourses) were critically integrated and often with dual or even multiple mediations for the purpose of individual creativity.

It was as Chen herself remarked matter-of-factly, ‘I have studied the tendencies and styles of various painting schools, but I always feel that I can’t rely on any of them.’”

On a somewhat related note, I would like to share a short piece I wrote for the December/January issue of Monocle about Mud Rock Ceramics, a very cool ceramics studio in Singapore. (h/t Rebecca for the link-up!)

Thanks for reading!

You're so right about those rambutans. They're succulent.

As for the politics... I have enormous confidence in China's ongoing confidence and ecumenical ability to absorb and engage with global culture. I mean, I know everything looks gross and nationalist in the news, but at least here in Fujian, there is an outward-bound connectedness to the world that makes me feel like all the -isms in the world will never stop these people gossiping about their relatives in Southeast Asia, Europe, America, wherever. Perhaps things are different in the cold grey wastes of the north, but as long as southern China exists, the world's in good hands.