eggs

what to make of them?

Felice Casorati was born in Novara, a city in Piedmont, in 1883, and died in Turin, a larger city in Piedmont, in 1963. He was a painter, but he also made sculptures and designed sets and dabbled in architecture and music. His paintings are often classified as Magic Realism and Neo-Renaissance, but he also has work reminiscent of Klimt, Cézanne, the Pre-Raphaelites, expressionism and Art Nouveau. Casorati painted women, landscapes, portraits, Fiat cars, nudes, and still lifes; he also painted eggs.

Egg in Italian is uovo; with the article, l’uovo. Simple, masculine (-o). The eggs is le uova; unusually, the plural form becomes feminine, but, even more unusually, uses the singular feminine -a for the noun and the plural feminine le (rather than la) for the article. This is highly irregular, and has no bearing on Casorati’s paintings, but I’m sure any fellow Italian learners reading this are nodding/shaking their heads, all too familiar with the tricky grammar of the egg.

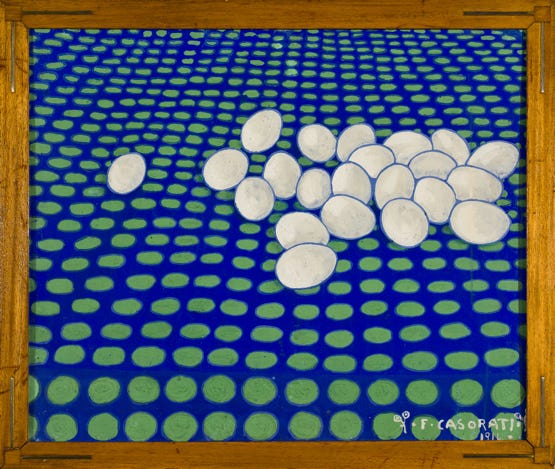

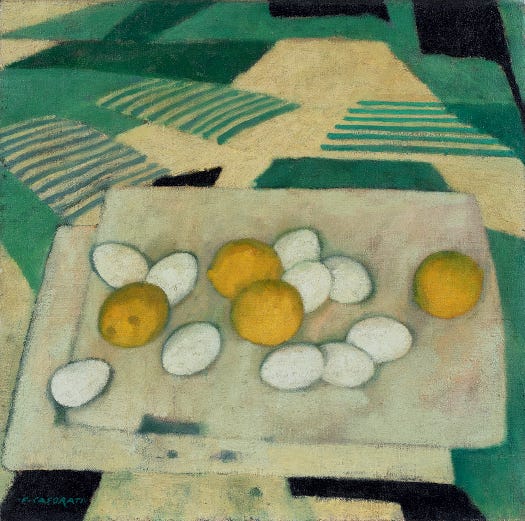

Casorati’s egg paintings span decades. At the outbreak of the First World War, he was painting eggs; near the end of his life, he was still painting eggs. One early egg painting is called Scherzo uova. Scherzo is joke (singular). Uova is eggs (plural). Joke eggs? Eggs joke? Surely egg joke. Egg play? But here it is:

I love Scherzo uova because even though it is the oldest of his egg paintings, it appears futuristic: whatever blue-green patterned cloth or carpet atop which the eggs rest evokes, for the viewer of 2024, CGI dots, green screens, popular visualisations of the Internet, the Matrix; and the eggs seem to float in this digital ether.

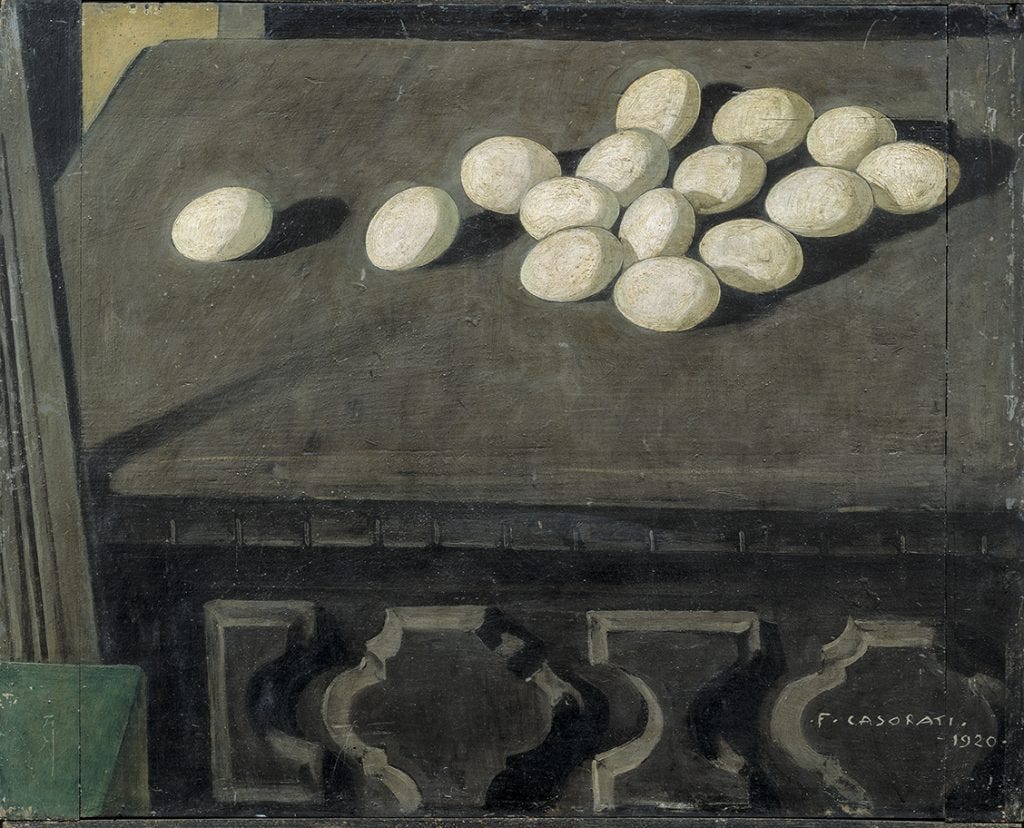

Six years later came Le uova sul cassettone, “The eggs on the dresser”:

Forty years later, Uova nel paesaggio, “Eggs in the landscape”:

Sometimes the eggs appear in the paintings without being referenced in the titles, like in Natura morta con l’elmo (“Still life with helmet”) from 1947, which also features a rare brown egg beside Casorati’s usual white egg:

In Fruttiera con limoni e uova (“Fruit bowl with lemons and eggs”) from 1959, the eggs nestle among lemons, though an errant egg on the table beside the fruit bowl assures the viewer that the eggs hold pride of place over their still life companion-rivals (and how could lemons hope to triumph over eggs in the battle of the oval-shaped, when the word oval itself (and its various tributaries, ovoid, ovate, oviform) derives from, of course, ovum — egg?). Even without this extra egg, the simple lemons cannot compete with the spectral eggs under whom they burrow. The eggs compel the eye to linger; they are even whiter than the white porcelain of their bowl. (This is not Casorati’s only painting of admixed lemons and eggs.)

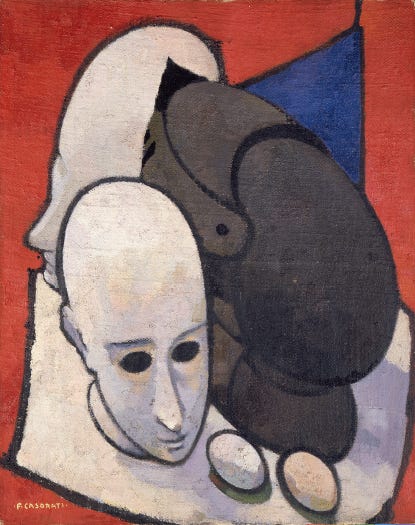

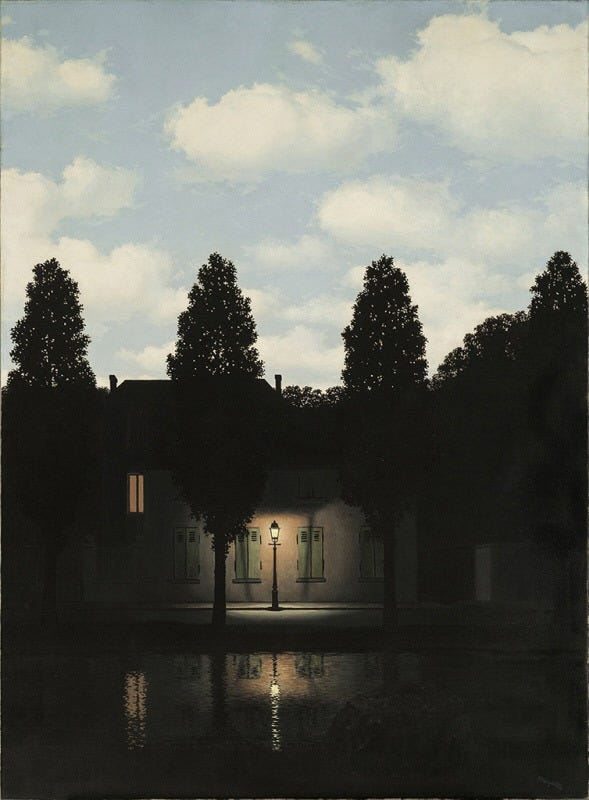

There is an eggness, even, to the paintings of his that lack eggs. By eggness I suppose I mean moods or qualities including but not limited to: unsettling, precarious/light/balancing, deadpan, cool-temperatured, enclosed, expectant, enceinte. Quiet in the same way that certain paintings of Magritte or Paul Delvaux are quiet: a loaded, ominous quiet, a static state that crackles with potential energy.

There are no eggs in Casorati’s Silvana Cenni, but there is a woman with a suspiciously egg-shaped head:

Casorati never painted a fried egg or a scrambled egg or an omelette; he never painted a bleeding yolk. His eggs have no cracks; their fluids do not run. (“I adore static forms,” he once said.)1 But why was he so into eggs? I don’t know. It is a mystery, unhatched.

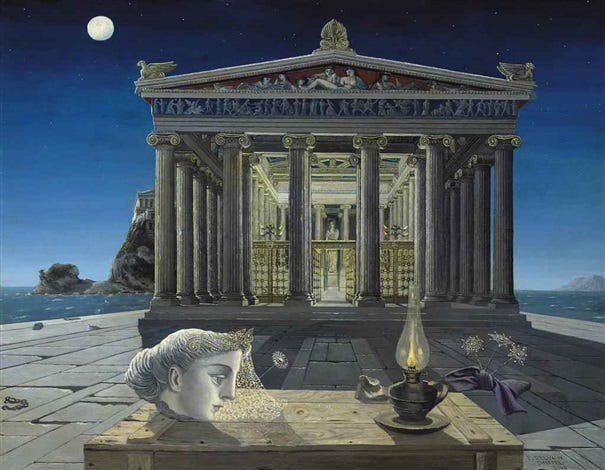

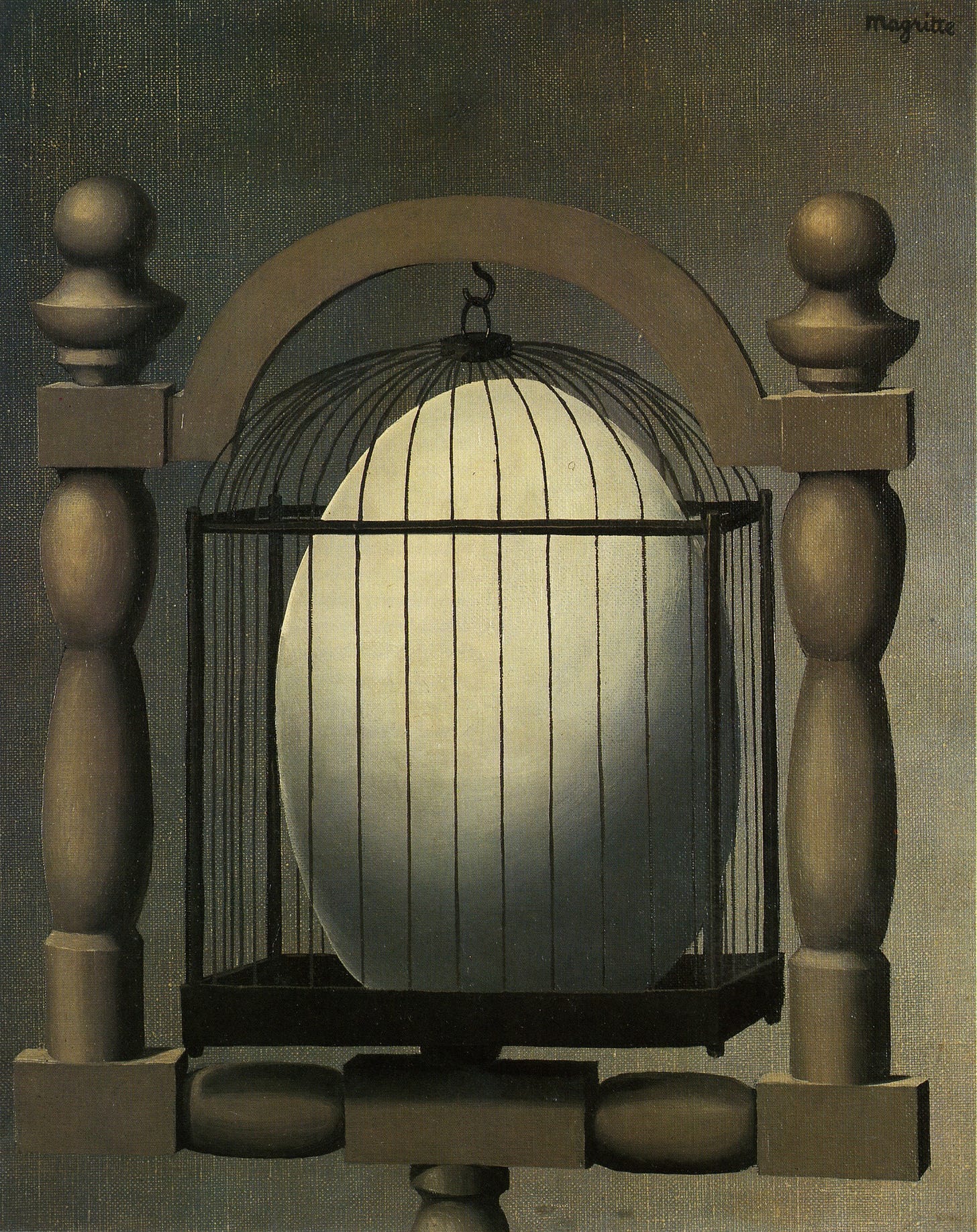

Magritte also painted an egg once, and named the painting after a Goethe novel:

Thanks for reading!

https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/ab-art-base/felice-casorati-life-and-works-of-the-great-painter-of-magic-realism