in search of the blood red sublime

flaubert, porcelain, and the most elusive color in the world

In Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, the pottery manufacturer Jacques Arnoux spends a lot of time and resources trying to recreate the copper-red glaze he has seen in certain Chinese ceramics.

“Ah! how tired I am, my dear fellow! It will be the death of me! However, I can tell it to you—to you!”

He bent towards Frederic’s ear in a mysterious fashion:

“I am trying to discover again the red of Chinese copper!”

And he explained the nature of the glaze and the little fire.

Many pages later, he’s still at it:

Arnoux took a great deal of pains with his earthenware works. He was endeavouring to discover the copper-red of the Chinese, but his colours evaporated in the process of baking. In order to avoid cracks in his ware, he mixed lime with his potter’s clay; but the articles got broken for the most part; the enamel of his paintings on the raw material boiled away; his large plates became bulged; and, attributing these mischances to the inferior plant of his manufactory, he was anxious to start other grinding-mills and other drying-rooms.

He never succeeds. The last we hear of it, Arnoux has abandoned the effort, and Arnoux’s wife is showing the underwhelming fruits of his trials to Frederic, the protagonist, who spends most of the book deceiving and manipulating Arnoux in order to seduce said wife.

In order to divert his attention with something of an amusing nature, she showed him the species of museum that decorated the staircase. The specimens, hung up against the wall or laid on shelves, bore witness to the efforts and the successive fads of Arnoux. After seeking vainly for the red of Chinese copper, he had wished to manufacture majolicas, faiënce, Etruscan and Oriental ware, and had, in fact, attempted all the improvements which were realised at a later period.

[…]

He now made letters for signboards and wine-labels; but his intelligence was not high enough to attain to art, nor commonplace enough to look merely to profit, so that, without satisfying anyone, he had ruined himself.

Oof. Perhaps Arnoux would been comforted to know that achieving the coveted “copper-red of the Chinese” also frustrated the Chinese themselves. During the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) artisans in Jingdezhen, the porcelain manufacturing capital of China, perfected the famous blue and white glazed “china” porcelain. Vast consignments of bowls and plates and cups and jugs were sold around China and shipped abroad to buyers in Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

Red glazes — made from copper oxide — also started to appear. This may have been spurred by a shortage of cobalt (necessary for the blue glaze) and/or an emperor’s personal preference for the color. But red-glazed porcelain came nowhere near the quantity or quality of the blue and white. The copper oxide pigment was incredibly sensitive to changes in temperature and the surrounding air, and required extremely precise kiln conditions. The thickness of the glaze or the particular mixture of pigment and other ingredients could mean the difference between a bright red and a brownish, greyish, or liver-hued vase. The glazes bubbled and cracked and the red-shaded lines bled and leaked, ruining painstakingly intricate patterns and necessitating simpler designs.1

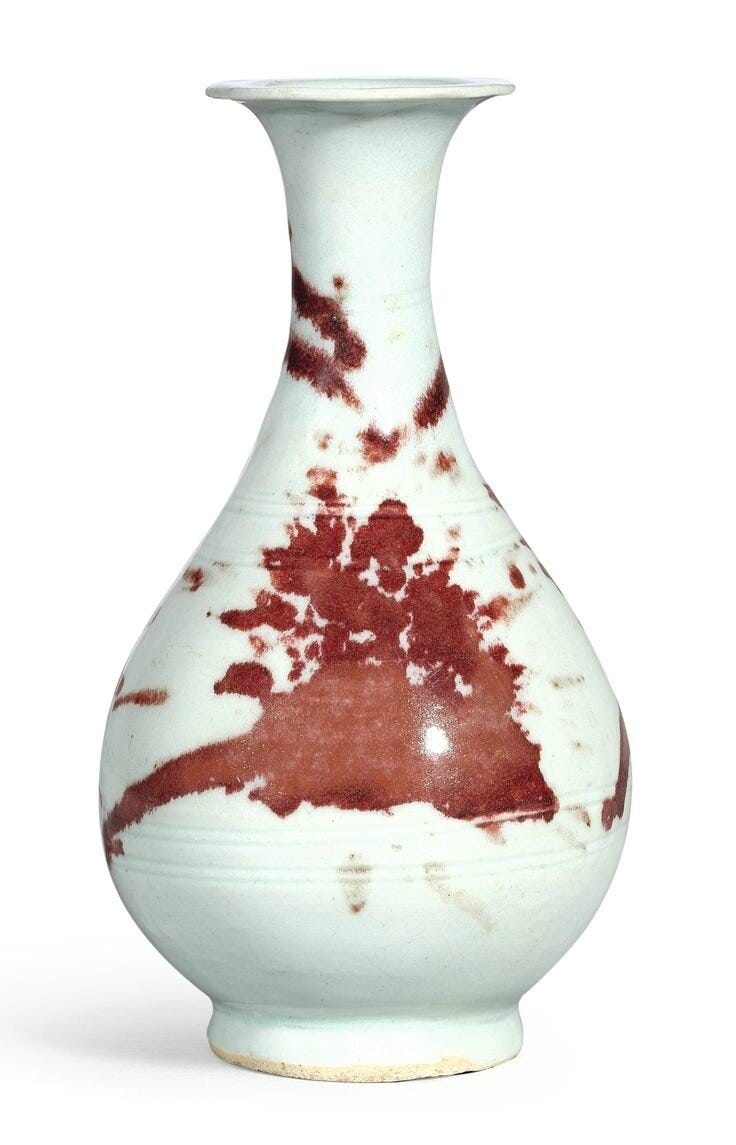

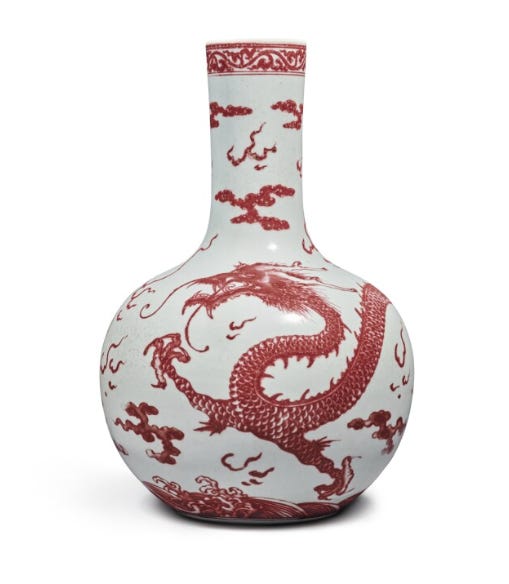

The difficulty of obtaining a proper red glaze is evident in the contrast between the blue and white porcelain and the copper-red porcelain from the same era:

Three words appear again and again in descriptions of the copper-red porcelain of the Yuan Dynasty: “experimental”, “unstable”, and “difficult”. This sounds exactly like Arnoux’s experience. But what exactly was he trying to emulate?

Hundreds of years had passed between the copper-red “misfires” (as in-kiln errors are literally called) of 14th century China and Arnoux’s own misfires in mid-19th century France, when Sentimental Education takes place. Arnoux would have seen later, more skilful iterations of copper-red glazed porcelain.

The Yuan (1271-1368) and the succeeding Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties exported ceramics around the world. China’s ceramics manufacturing hubs were near-industrial in organization, technology, efficiency and sheer scale. These city-wide setups were not too far from what one might term a “factory” or a “production line”. There were imperial kilns which produced porcelain for the emperor, manufacturers for the domestic Chinese market, and manufacturers dedicated solely to export markets, able and willing to make whatever shape, size, color and pattern their customers required. They made porcelain with Islamic motifs and Arabic calligraphy and inscribed plates with the names of Mughal emperors. They made platters larger than any in China, for clients in Turkey and Iran and Java who used them for communal meals; they made ceramic traveler’s flasks for pilgrims in Syria.

By the 17th century, Europe — largely absent from the globalised commercial dealings of the previous Yuan Dynasty — had become a big export market. Now the craftspeople at Jingdezhen were etching winged cherubs and Latin mottos and Portuguese coats of arms on their porcelain. Of course they were also selling the classic blue and white peonies and dragons and qilins. Europeans loved the Chinese stuff, too.

Balzac’s 1836 novel L’Interdiction sets the word “chinoiserie” down in print for the first time; 40 years later it begins to appear in French dictionaries. By the mid-19th century, the chinoiserie craze in Europe had peaked, but — at least in the affluent Paris of Sentimental Education — it remained a coveted aesthetic. In Flaubert’s novel there appear Chinese shot-silk parasols with carved ivory handles, Chinese ornaments and lacquered screens, Chinese-style anterooms in Parisian homes with painted lanterns, decorative sprigs of bamboo, and tiger skins. And of course Chinese porcelain, and the elusive copper-red glaze.

Arnoux would not have known about the early 14th century misfires, the pale brown-greys and the faded illustrations. By his time, the Jingdezhen artisans had gotten much better at handling the volatile pigment through new techniques and ingredient mixtures and centuries of practice. He was probably comparing his own attempts to objects like this porcelain vase from the 18th century:

Even the Sotheby’s catalogue note for this vase makes note of the challenges that defeated Arnoux:

Due to the difficulties of firing copper red successfully, ceramics painted with underglaze red designs are comparatively rare. The present vase showcases the great technical advances of the High Qing dynasty that enabled the success of this vibrant decorative mode.

Here’s another testament to the difficulty, from a porcelain specialist:

The problem with all these glazes are that copper is very volatile and it is just very difficult to fire a glaze based on copper so as it turns out pure red when finished. The success rate of wares with specifically copper red glazes has up until today typically been very low.

In Sentimental Education, Arnoux is not presented as especially sympathetic (not that any character in Flaubert’s novels escapes from the author’s cool and ironic judgment); he’s a bit of a fool, oblivious to Frederic’s designs on his wife, frivolous and ineffectual in his pursuit of aesthetic beauty and business success. All of these traits are exemplified by his failed attempt to achieve the “copper-red of the Chinese”. The whole thing is really just a comic sub-subplot.

But in fact, Arnoux was trying to do something very difficult, something that the greatest artisans in the only country in the world capable of producing porcelain at such a high standard took generations to perfect.

And it’s not as if they cracked it one day and solved the problem forever, either. The beautiful copper-red glazes achieved by the “great technical advances of the High Qing” mentioned in the Sotheby’s catalogue were themselves considered lesser imitations of red-glazed porcelain produced in the 1420s and 1430s, and then basically never again.

The red porcelain of the earlyish 15th century Ming dynasty is widely considered the high-water mark of the copper-red glaze. In Chinese it is called xianhong 鮮紅 – “fresh red” or jihong 祭紅 – “ceremonial red”, because the pieces were used as altar vessels. A remarkable feature of these pieces is that they are monochrome. No dragons, no phoenixes, no landscapes, no calligraphy. Just color.

There are just a few dozen surviving examples left. In the later Ming, the ability to produce quite such a vibrant red was lost; centuries later, during the Qing dynasty, Jingdezhen ceramicists diligently tried to match the glossy blood red their antecedents had achieved. They came close, but never really recreated it. Here is one of the copper-red glazed porcelain dishes from that high-water mark era:

If you’ll indulge me, I will end this missive with an extended excerpt from the National Museum of Asian Art’s beautifully written history of this dish and others like it. With such context Arnoux’s trials do not seem so silly at all.

Chinese monochrome porcelains are among the greatest achievements in world ceramics, and no color is more sought-after or admired than the luscious copper-red glaze of the early fifteenth century, especially of the Xuande reign. Although imitated later, it was never again realized. During the short period when this glaze was perfected, the imperial court presided over a populous, cosmopolitan state actively engaged in global trade and overseas exploration.

[…]

The superb, difficult-to-accomplish red of this dish demonstrates the exacting standards and extent of imperial control that reached from the capital in Beijing to the far-away kilns in Jingdezhen, where the dish was produced.

The triumph of Xuande copper-red-glaze lies in the combination of color and texture—raspberry (some call it—cherry) red, thick and velvety. The tactile quality of the surface is created by millions of trapped bubbles in the glaze that suffuse it with tiny speckles and subtle irregularities in color. Some minute pitting from burst bubbles creates the typical early 15th century "orange peel" surface.

[…]

The complexity in using difficult-to-control copper severely limited the number of successful firings; off-color fragments excavated from the early Ming imperial kiln site record many failed attempts.

[…]

Production of this high-temperature red glaze is extremely challenging and was pursued consistently beginning only in the fourteenth century, reaching a breakthrough in the Xuande period. The colorant is finely ground copper oxide mixed into the glaze. During firing, reduction of the copper ions to colloidal copper metal and phase separation in the glaze produced a complex network of reddish and yellowish glasses to create the mottled effect. Scientific analysis shows differences in the percentage of copper (and occasional additions of other metal oxides) even within the short period of the first half of the 15th century when the glaze was attempted, and suggests considerable tweaking and experimentation devoted to producing this rich red.

Changes also occurred to the base glaze: adding slightly more calcium facilitated the escape of bubbles and dissolving of batch material that otherwise veiled the red. The percentage of copper was reduced to about half of one per cent (of which possibly half volatilized and disappeared during firing). With too little copper, the color was pale; with too much, it became livery. Some small kilns at the imperial site are now thought possibly to have been dedicated to the red wares, which required slight over firing for success and so could not be mixed easily with other types of wares.

Extensive scientific analysis since 1985 is bringing scholars close to understanding how Xuande copper-red glaze was achieved, but it still retains a touch of mystery, not least of all in imagining how potters in the early fifteenth century were able to control so expertly the many challenges and complexities of its production. The remarkable beauty of this copper-red dish inspires us to reflect on China’s place as world leader in the art of porcelain.2

Thanks for reading!

https://www.chinese-porcelain-art.com/pages/articles-top-level/antique-chinese-ceramics-and-works-of-art/the-use-of-copper-red-in-chinese-ceramics/

https://asia.si.edu/explore-art-culture/collections/search/edanmdm:fsg_F2015.2a-b/

Last year I had the opportunity to visit Jingdezhen referred to in this article. It is a great combination young ceramic artists and great museums but is not on most tourist itineraries. This article makes me want to visit again.

Thanks for such an interesting and informative piece. In the late 1980’s, I purchased a beautiful red porcelain vase from a pottery shop. The woman there told me red is an extremely difficult color to achieve with porcelain. What I have is certainly not the Chinese red, having a much brighter hue, but I think I’m about to go down a very deep hole to learn more about red porcelain.